- Home

- Carlos Rojas

The Valley of the Fallen

The Valley of the Fallen Read online

The Valley of the Fallen

The Valley

of the Fallen

El Valle

de los Caídos

CARLOS ROJAS

TRANSLATED FROM THE SPANISH

BY EDITH GROSSMAN

The Margellos World Republic of Letters is dedicated to making literary works from around the globe available in English through translation. It brings to the English-speaking world the work of leading poets, novelists, essayists, philosophers, and playwrights from Europe, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East to stimulate international discourse and creative exchange.

English translation copyright © 2018 by Edith Grossman.

Originally published as El Valle de los Caídos, copyright © 1978 by

Carlos Rojas Ediciones Destino.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office).

Set in Electra and Nobel types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017944084

ISBN 978-0-300-21796-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For María Dolores and Giovanni Cantieri

The English edition is dedicated to Marina, and Sandro Vasari, as well as to Edith Grossman, who translated their book

Comme un pâtre est d’une nature supérieure à celle de son troupeau, les pasteurs d’hommes, qui sont leurs chefs, sont aussi d’une nature supérieure à celle de leurs peuples. Ainsi raisonnait, au rapport de Philon, l’empereur Caligula; concluant assez bien de cette analogie que les rois étaient des dieux, ou que les peuples étaient des bêtes.

—Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du contrat social

CONTENTS

The Absurdities

The Dream of Reason

The Family of Carlos IV

The Monsters

The Prince of Peace

The Disasters of War

The Dream of Reason

May 3, 1808, in Madrid

The Monsters

The Duchess of Alba

Tauromachy

The Dream of Reason

Wild Bull

The Monsters

Pepe-Hillo

The Caprices

The Dream of Reason

Blind Man’s Bluff

The Monsters

The Duchess of Osuna

Furious Absurdity

The Dream of Reason

A Quarrel with Cudgels

The Monsters

The Desired One

Timeline

The Valley of the Fallen

THE ABSURDITIES

THE DREAM OF REASON

The Family of Carlos IV

In July 1800, Goya receives the fee for the most celebrated of his portraits, The Family of Carlos IV. According to the date payment was made, Josep Gudiol deduces that the artist would conclude his canvas that spring, the first of the century. Goya begins by making a sketch, a “rough,” of each member of the royal family against a red-wash background. Those of Infanta Josefa and Infante Antonio Pascual, the king’s sister and brother, are in the Prado. In these studies, which are authentic paintings, the painter leaves clear evidence of his moral purpose in portraying the entire ensemble. He will not idealize or caricature his models. He feels as far from mockery as he does from flattery. He limits himself to representing the monarchs and their kin as Velázquez painted court jesters: detailing their physical flaws in order to reveal their inner world. And yet the results achieved by Velázquez and Goya are completely antithetical. While Felipe IV’s buffoons reveal their sensitivity and tragic sense of life through their deformities, Goya’s royal imbeciles, as Aldous Huxley will call them in another century, lay bare in their features the stupidity, ambition, and duplicitous cunning that dwell within them.

Almost all the “roughs” contain a complete depiction of the subjects. The only exception is the sketch of the head of Prince Don Carlos María Isidro, who will ignite the so-called Carlist Wars in the next generation when he competes with his niece, Isabel II, for the throne. In the sketch a boy’s head looks out at us, with blond eyebrows and a glance almost as obscure as that of his brother Fernando, the crown prince, though much more willful and devoid of the glint of sadness that in the eyes of the firstborn is mistaken for rancor. In the family portrait, however, Don Carlos, pale and half hidden behind Fernando, seems an extraordinarily and prematurely aged adolescent: almost a dwarf, mockingly invested with the blue-and-white sash of Carlos III, his features withered and arrested on the verge of puberty.

Although the king stands in the center of the painting, a step ahead of the others, the queen is the real protagonist in this grotesque tragedy. Wearing a low-cut dress, her bosom, wig, and ears heavily bejeweled, she smiles disagreeably with tight, almost invisible lips. At the time that Goya is painting The Family of Carlos IV, in March 1800, the French ambassador writes to Napoleon: “The Queen arises at eight, receives the nursemaids of the younger children, and arranges their outings. She writes every day to the Prince of Peace, telling him everything. After the King’s breakfast, the Queen is served hers. She eats alone and has a special cuisine because she is missing all her teeth. Three experts continually retouch her false teeth. The entire royal family attends the bullfights. The Queen is so superstitious that she covers herself with relics during a storm.” A great, ugly mythic bird from The Caprices seems to metamorphose into the head of María Luisa right in the middle of the canvas. Napoleon is enthusiastic about that august head when he conquers Madrid. “It is incredible! Never before seen!” he usually says and then laughs when he describes the canvas. The monarchs, on the other hand, are pleased with Goya’s work. On June 9 of that year, María Luisa writes to Godoy: “Goya begins my portrait tomorrow. The rest, except for the King’s, are already finished and show a great resemblance.” Two weeks later she writes to him again: “Goya has done my portrait. He says it is the best of all. Now he is preparing the portrait of the King, in La Casita del Labrador.”

In the center of the canvas, treated with a resinous solution and painted in oils as transparent as watercolors, María Luisa has her arm around Infanta María Isabel and holds the hand of Infante Francisco de Paula. Court gossip attributes their paternity to Godoy. At this time the infante is only eight years old. Antonina Vallentin notes on his face a tenacious, somber look, inexplicably perverse on the face of a child. His resemblance to the portrait of Godoy in his youth, the work of Esteve, is startling. Two years later, Infanta María Isabel will marry the prince of Naples. Her mother-in-law, Queen Carolina, confesses to Alquier, the French ambassador, that the Infanta is manifestly Godoy’s daughter and has inherited his appearance and expressions. The Neapolitan sovereign does not think highly of her son-in-law, the prince of Asturias: “The Prince does nothing, he does not read, he does not write, he does not think, nothing. Nothing . . . And this is deliberate, for they wanted him to be an idiot. The vulgarities he commits constantly, with everyone, are mortifying. The same is true of Isabel. They were allowed to grow up in the greatest ignorance, and what was done to them is a disgrace.

Since María Luisa rules despotically in Spain, she always fears that someone will want to meddle in politics or her affairs.”

The king looks like a wax statue of himself. He is now fifty-two, two years younger than Goya, who portrays himself at the other end of the painting, like Velázquez in The Ladies-in-Waiting, painting it and painting himself. Yet one would say the monarch is much older than the man who immortalizes him in this portrait. He has put on weight and aged prematurely after having been very vigorous. His blue eyes, lost in vacancy like those of a blind man, are somewhat darker than those of his brother, Infante Antonio Pascual, who, peering out from behind His Majesty, resembles the caricature of a caricature. When Princess María Antonia of Naples, now Fernando’s fiancée, eventually gives birth to a stillborn child, her only one, María Luisa again writes to Godoy: “The child was smaller than an anise seed. To see him the King had to put on his reading spectacles.” María Antonia herself is found between Fernando and María Isabel, her head turned toward the paintings on the wall. She has not come yet from Naples, and Goya cannot complete her profile without seeing her. He will never paint her, and the portrait is still incomplete. Behind Fernando and María Antonia appears the head of the ancient Princess María Josefa, sister of the king and Infante Antonio Pascual. An observer would think that one of those mirrors in which Goya’s old witches look at themselves, while winged time prepares to sweep them away, has brought the image of one of those sorceresses back to life. Adorned with long gold earrings and peacock feathers on her head, the apparition is smiling. She has a blemish on one temple and eyes as blue and glassy as those of her brothers.

Four beings crowd together at the right. We see only the profile of the monarchs’ oldest daughter, Princess Carlota. She will be queen of Portugal, and one of her daughters, Isabel de Braganza, will rule in Spain, wed to her uncle Fernando VII, in his second marriage. The duchess of Abrantes says that Carlota is quite deformed: one leg is longer than the other, and she is hunchbacked as well. In front of Carlota we have her sister, María Luisa, holding a child in her arms. She has small features and an artless glance. Her face is pleasing without being beautiful. A pillow on which she holds her baby does not hide her twisted waist. She is accompanied by her husband Prince Luis de Borbón Parma, heir to the duchy of that name and María Luisa’s nephew. A tall, blond boy with lively eyes and fleshy lips, in whom there is already a suggestion of obesity. He is also an epileptic.

In the background of the painting are two other paintings; as in the background of The Ladies-in-Waiting, there is a mirror, which perhaps is also a painting although it could be taken for a window. In The Family of Carlos IV, two large canvases hang on the wall behind the fourteen figures. Both are by Goya in Goya’s canvas, though they do not appear in Gudiol’s complete catalogue. One is a trivial blurred landscape, perhaps a work of his youth, when the painter believed he accepted the world as his time seemed to accept it, in the glow of the enlightenment and at the hour of Blind Man’s Bluff and outings along the Manzanares. In the other, darkened by time, are three indistinct figures. Until 1967 no one paid very much attention to it. However, it contained the final moral key to The Family of Carlos IV.

In June 1967, the Prado decided to restore Goya’s canvas. In December, the surprising results of that undertaking were made public. In the painting represented in the background, along with the landscape of the stream and birches in the glow of enlightened harmony, there appeared a confused orgy of giants. In that canvas within a canvas, with large brushstrokes that come from Velázquez and precede or at the same time invent impressionism and expressionism, Goya displays a naked titan frolicking with two half-naked women as enormous as he is. The male’s face is undoubtedly Goya’s, according to Xavier de Salas, director of the Prado. No one dares to contradict him.

When Goya paints The Family of Carlos IV in 1800, he has been almost completely deaf for eight years, and living on loans of life. In 1792, the syphilis that perhaps he hadn’t known until then he had contracted in his early youth, infects his inner ear and has him at death’s door for two long years. Malraux compares him then to one of those sick people who, saved in their death throes, become mediums. At the end of the crisis, imprisoned in his silence, Goya would have an aura of the next world. The truth is precisely the opposite, because Goya conjures living specters, not dead phantoms. This is why his monsters seems so vraisemblables, so believable, to Baudelaire. In his deafness he describes the dark night of the soul, where life hides its most terrible truth. Death will reveal itself to him from the outside, sixteen years later and on another principal date in his life, May 2, 1808, when the savage battle in the Puerta del Sol between the Spanish people and Murat’s Mamelukes is recounted to him.

From his brush with death Goya has learned to judge so that he may be judged. Faced with reason, which, after all, dreams of hobgoblins and monsters in its nightmares, Goya proclaims the truth of man, inhabited by monsters, incapable of reconciling with the world if he does not reconcile first with himself. Like death, truth is common to everyone; like syphilis, it is also contagious. Nineteen years later, Goya, the old convert to enlightened harmony and the idealist of reason, will record all the demons of his people on the walls of his house, so that neither he nor history can forget them. His belief in truth as the only measure and synthesis of man is passed on to the monarchs, who willingly accept seeing themselves as Goya saw them, not as they believed they were. The only compromise between the painter and his models is reduced to hiding Princess Carlota’s hump behind the Prince de Borbón Parma. But the deformed waist of her sister María Luisa is as visible as all the flaws of her kinfolk.

In the painting at the back of the room, Goya leaves his own confession. There, and in his orgy with the two prostitutes, this deaf man silently proclaims his condition as a man, since nothing human is alien to him. He does not condemn the flock of dressed-up caricatures he has just portrayed for posterity, because he does not imagine himself as better or worse than any of them. He knows very well that in a similar orgy he contracted the syphilis that gnaws at him, deafens him, and has destroyed four of his children. His guilt, the guilt of Saturn, presides over this last judgment, which is, at the same time, the noblest document of the eighteenth century. A last judgment of the living, more profound than Michelangelo’s judgment of the dead, according to Ramón Gómez de la Serna. A century and a half later we read in a now forgotten book: “With Goya’s eyes we are to see ourselves in his goblins and in his Monarchs, in the two waiting rooms of our destiny. Goya’s ethical precept opens each day with the doors of the Museum. It is the first principle of an indispensable, even incomprehensible dialectic, in which he attempts to anticipate the final salvation of man: ‘You will love your neighbor, the monster, as yourself.’”

March 16, 1828

And His Majesty the king said to me:

“What is your idea of happiness on earth?”

“Dying before my son Xavier,” I replied immediately. “My wife and I had already buried four others before I had to bury her too during the wartime famine. I don’t want to lose this one.”

He burst into laughter without letting go of the cigar he held between his teeth, as yellow as a lamb’s. He was close to, or had already turned, forty. Only when I painted him, for the last time and at his request, did I become fully aware of how deformed his face was, large-jawed, fat-cheeked, asymmetrical beneath his long black eyebrows. And yet in his slightly crossed eyes gleamed a guile that was in no way dim-witted. He had been the most loved man and was the most despised in this country that always charges forward when it is time to kill or reproduce. I supposed that our hatred and our love made him equally proud. In fact, he almost confessed as much to me on the previous afternoon, when I finished his portrait. He said: “You were a traitor and pro-French during the invasion. I overlooked it then, twelve years ago now, as I have forgiven you this time when I learned you were returning from exile, because you are even greater than Velázquez. Tomorrow you

return to the palace to dine alone with me.

“You’re a cynic. You believe in nothing. Nothing at all. ‘Nothing’ says the paper that the skeleton brings back from death in one of your etchings. There was a time when you would have been burned at the stake for much less.”

“I’m not going to believe in you and your divine right over all of us. We know each other too well.”

The truth was that everybody knew him. Before the war, and at the trial in the Escorial, when he and his coterie were accused of conspiring against Godoy, our sausage-maker and Prince of Peace, he wrote incredible letters to his parents, the king and queen, which would be repeated afterward by all the gossipmongers. ‘Mama, I regret the horrific crime I have committed against my dear parents and sovereigns and beg with the greatest humility that Your Majesty deign to intercede with Papa so that he will allow his grateful son to kiss his royal feet.’ His mother shouted that he was a bastard, and to confirm his status he denounced all his accomplices. During the war and in the Castle of Valençay where, according to him, the French held him prisoner, he again betrayed those who had conspired to liberate him. At the same time, he congratulated Napoleon for his triumphs in Spain and asked that he make him his adoptive son by marrying him to a princess of the Imperial House. Then we also learned that in Valençay he received music and dance lessons when he wasn’t hunting, fishing, or riding horses in the castle’s parks, and dedicated his evenings to his favorite leisure activity, embroidery with beads and bugles. And yet, if we think about those times, perhaps it would be better not to recall him or any of us, for that matter. When remembering them, one could say that only murderers knew how to preserve their dignity in this unfortunate land of ours.

“We know each other too well. No doubt about that,” he agreed with slow nods, suddenly pensive or regretful. “You didn’t want to bury your children. I was never happier than when I learned my parents were dead. It’s been almost seven years since my mother died in Rome, and ten days later, in Naples, my father followed her to hell. Only then, and for the first time in my life, did I feel free. Then I told myself no, to really be free, they would never have engendered me. Only those who have never lived are free, because even the dead suffer their punishment. The rest of it, including the crown, is a line in the water and the intrigues of courtiers.” He paused for a moment, looking into my eyes, and belched. “It’s a gift to speak to a deaf man: like confessing to a brick wall.”

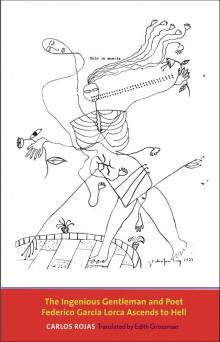

The Ingenious Gentleman and Poet Federico García Lorca Ascends to Hell

The Ingenious Gentleman and Poet Federico García Lorca Ascends to Hell The Valley of the Fallen

The Valley of the Fallen